Classifying Personality with Machine Learning

In this project, I demonstrate a technique to classify a person’s Big 5 personality traits based off of 20-minute stream-of-consciousness essays. I achieved an average accuracy of 58% across the five personality categories by using Sentence-BERT embeddings coupled with small neural network classifiers. Although this is slightly less than the 60% accuracy achieved by other BERT-based techniques, my model represents a 1000x reduction in complexity from these other methods. In addition to demonstrating the power of Sentence-BERT, this reduction in complexity is an important step in making these types of models more distributable to end users. The code for this project is available on GitHub as a Google Collaboratory notebook.

Disclaimer

While I present this work in the context of psychology, this is a substantial deviation from the areas of research in which I have been formally trained. This work has not been peer reviewed. If these results seem relevant to your work, I’d instead point you to Deep Learning Based Fusion Strategies for Personality Prediction.

Background

The Big 5 system classifies a person’s personality according to openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Where a person falls on this scale (and how this changes with time) can have implications over a wide range of topics, such as academic achievement and mental health. Although the model isn’t without its criticism, studies relating to the Big 5 are prevalent in psychology.

Typically, a person is assigned a personality score after responding to questions on a questionnaire. However, there has been considerable effort spent as of late towards developing alternate assessment techniques with deep learning. It is to this task that I devote myself in this project: can a short essay from your stream-of-consciousness be used to predict your personality type?

Throughout this project, I compared my work to that of El-Demerdash et. al. in their paper “Deep Learning Based Fusion Strategies for Personality Prediction”. In this work, they attained 61.85% accuracy in determining a person’s personality type from their essays. To achieve this, they used an ensemble of three large language models(LLMs), as well as a “fused” training dataset consisting of both the stream-of-consciousness essays and user’s facebook activity. That is a more intensive project than I undertook, but as they recorded their intermediate results, the paper still serves as an apt point of comparison.

In particular, they report the result of fine-tuning the BERT LLM on only the stream-of-consciousness data, after which they achieved 60.43% accuracy in personality classification. This is most similar to my attempt, described further below, based around building light classifiers on top of Sentence-BERT embeddings.

The Data

The dataset used in this project consists of 2,467 essays collected by James Pennebaker et al.. Students wrote down their stream-of-consciousnesses, then took a standardized personality test. Often referred to as the Essays Dataset, this has become one of the most prominent datasets used to build and measure automated personality classification systems. myPersonality, a dataset consisting of Facebook content coupled with the user’s personality type information, is also quite prominent. However, this dataset’s maintainers stopped sharing it in 2018, and I felt it best to respect their withdrawal by not using it in this work.

Data Preparation

With five binary personality labels, there are a total of 32 unique personality types. I used a stratified shuffle split on these 32 categories to implement an 80/20 train-test split of the Essays Dataset. The training data was further divided, again using the stratified shuffle split, into an 80/20 train-valid datasets. El-Demerdash et. al. used 90/10 splits, but given the small number of samples in this dataset, I felt the 80/20 ratio justified.

BERT

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, or BERT, is a large language model (LLM) introduced by google in 2018. BERT was originally trained to predict masked words in a sentence, and to tell if two sentences likely followed each other in a string of text. However, it was created with the assumption that it would be fine-tuned to perform specific tasks, such as aiding Google searches.

This project uses Sentence-BERT, a variation of BERT trained for semantic text similarity tasks. Sentence-BERT takes a sentence or short paragraph as input, and outputs a point called an embedding in 384-dimensional space. The magic of Sentence-BERT is that these embeddings can be compared via cosine similarity or Euclidean distance to determine if they convey similar meanings.

My Method

My classification technique was a two step process: embedding the paragraphs with Sentence-BERT, and then running these embeddings through binary classifiers.

Embedding

The version of Sentence-BERT I used, paraphrase-MiniLM-L6-v2, is limited to sequences of 128 tokens (each token typically represents a few letters). Concerned about running over this limit, I used Python’s Natural Language Toolkit to split the paragraphs into individual sentences, ran the sentences through Sentence-BERT, then took the average of the resultant embeddings. I refer to the average embedding as the paragraph-level embedding.

I experimented with principal component removal, in an analog SIF-embedding. While I find this technique very interesting, it did not considerably improve the performance of my classifiers. I think this is consistent with the underlying justification for using SIF-embedding in the first place, but the topic is complex enough to warrant its own discussion. Keep an eye out for a companion article from me in the future! In the mean time, check out the accompanying notebook for further explanation.

Classification

After forming paragraph-level embeddings for each essay, I tested three different classification techniques: a random forest, a dense neural network with a 50% reduction in neurons at each level (which I will refer to as 1/2-NN), and a dense neural network with a 75% reduction in neurons at each level (1/4-NN).

Random forests are my favorite starting point for classification tasks; they are able to work on data that hasn’t been transformed (such as to have zero mean and unit variance), are resistant to over fitting, and can provide estimates on the relative importance of different features in the dataset. While constructing this classifier, I left most of the parameters at their Scikit-Learn default. Of particular importance, I drew with replacement the same number of samples which were in my training dataset, and randomly selected \(\sqrt{384}\) features to generate each tree. Using bootstrapping and multiple cores to speed calculation, I scanned ensembles of up to n=1000 trees, and used the out-of-bag samples as an estimator of model performance (however, in this regime of many features and few examples, the out-of-bag error rate is extremely pessimistic). I eventually settled on an ensemble of 800 trees, after which I trained the final classifiers on a set of both the training and validation data.

The neural network classifiers are composed of multiple dense layers. 1/2-NN consists of eight layers, with the structure 192-96-48-24-12-6-3-1 for a total of 98,683 trainable parameters.

1/4-NN consists of four layers, with the structure 96-24-6-1 for a total of 39,445 trainable parameters.

Both neural networks used the LeakyReLU activation function, and were initialized using He Normal Initialization.

The final output neuron of each network used a sigmoid activation function to produce a probability between 0 and 1.

I used the Nadam optimizer, with the step size determined by scanning a range of values, and choosing a size 1/10 the value where the minimum loss occurred (see the find_learning_rate function in this notebook, meant to accompany Hands-on Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras and TensorFlow).

This resulted in a step size \(2 \times 10^{-4}\) of for 1/2-NN, and for \(2 \times 10^{-3}\) for 1/4-NN.

Both neural networks were trained with early stopping, and weights were rolled-back to the point of lowest validation error.

Results

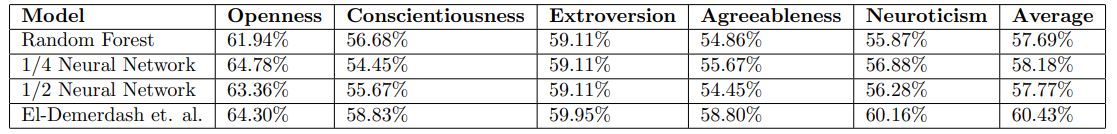

The above table shows a comparison of the different classification techniques. The last row is from the “BERT” row of Table 5 in El-Demerdash et. al.. These authors present a considerably more exhaustive study, and were eventually able to achieve an average accuracy of 61.85%. However, this involved more training data (fusing the Essays Dataset and myPersonality dataset), as well as an ensemble of three different classifiers, based on ELMo, ULMFiT, and BERT. The included row in this table shows their results from fine-tuning only BERT on just the Essays Dataset.

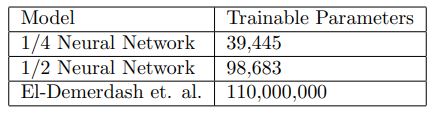

The above table shows the number of trainable parameters in each of the neural network approaches. These numbers represent a single classifier, and there is one classifier per personality type.

Discussion

My neural network classifiers are able to achieve an average accuracy <3% less than current state of the art classifiers, while reducing the number of trainable parameters by 1000x-2700x. This reduction in complexity is an important step towards making these models more accessible and easier to distribute. As an anecdotal example, it is interesting to compare this project with my prior one on fine-tuning GPT2 to generate scientific paper titles. The version of GPT2 I used contained 124 million parameters, and fine-tuning took enough computational resources that I ran into the GPU usage limit on the free version of Google Collaboratory. Training these smaller classifiers was considerably faster, and I never ran into usage restrictions (although, there are other factors at play here as well, such as different dataset sizes and me being more experienced).

Combining Sentence-BERT with these smaller classifiers has additional benefits over fine-tuning the entire BERT model. Because Sentence-BERT is standardized, the process of embedding a corpus of text can be more easily off-loaded to a remote, high-performance computing system, with the actual classification carried out on a local device. Further towards this goal, a single fine-tuned BERT model takes up 1.3 GB of disk space, meaning the full 5 classifiers would require 6.5 GB to store. In comparison, 1/2-NN requires up only 1.4 MB of disk space per model, and 1/4-NN requires a minuscule 644 kb per model.

Finally, this project demonstrates the power of Sentence-BERT embeddings. A model of BERT fine-tuned to classify “Openness” will only ever be able to classify openness, but the fact that this classification could so easily be pulled from Sentence-BERT embeddings implies that we are only just scratching the surface at what it is possible to achieve.

Ideas for the Future

One idea which particularly intrigues me is to look at a more complex methods of the embeddings of individual sentences into paragraphs. For example, one could imagine building a model to classify individual sentences, then averaging the classification of each sentence in a paragraph to predict the personality type of the writer. This could be further combined with clustering techniques to either remove outlier sentences, or perhaps even remove non-outliers.